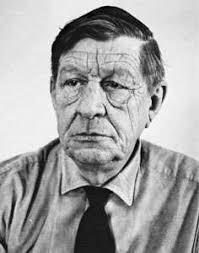

One of Alan Bennett’s mental companions (= people he perhaps never met, or who even weren’t alive, but always lived with) was the poet W.H. Auden. Bennett saw Auden at Oxford: his craggy face, his nasal voice. Later, Bennett decided to make Auden a character in his play The Habit of Art. It is based on Auden’s visit at Oxford in the winter of 1972 – he was after all Professor of Poetry In Residence from the year 1957 on (but he lectured for three weeks a year). Bennett analyses about the goal and devices of higher education: in the Oxford/Cambridge context seeing a “National Treasure” and being in the atmosphere of Great Men is considered good for students, even if The Famous One’s lectures are boring and repetitive. Were the Auden lectures boring and repetitive? Bennett says that Auden thought he has found America, not Columbus, and he was the first man to travel to Iceland – these defining life experiences of Auden became his “repertoire”. As Prince Philip has said about the stories of his uncle Lord Louis Mountbatten: “They became a bit over-familiar during the years”.

This is the downside of the beautiful British Empire – the pompousness always ready to rise its not-beautiful head under the light surface of self-deprecation. The cavalier right to judge who is colonial or outsider or Other. See the Brexit as a reference point. I read from the Bennett diaries a story about handsome second-generation actor Simon Williams (see Upstairs Downstairs, a British coup of the world). Williams said that, in addition to all officer, clergyman, aristocrat and politician parts he has traveled through, he is in much demand as a character actor for “Etonian”. Which he can do, as he went to Harrow (not Eton, so there it is).

Bennett says about Funeral Blues, one of Auden’s famous poems, that it is not properly performed in the movie Four Weddings and A Funeral: as it is blues it should have blues rhythm. I tried to read it in blues rhythm. Tricky.

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead,

Put crêpe bows round the white necks of the public

doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood.

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

This poem may well describe Auden himself, and many a forlorn lover:

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

The Bennett play character Auden compares notes of their life experiences with character composer Benjamin Britten. Britten is writing an opera based on Death in Venice, and the libretto he may or may have not asked Auden to write is one clashing point. Auden of this play is as untidy as his real self was: the story of the menu of the week on his tie is not apocryphal. Yet he was a stickler for punctuality – contradictions.

At the same time as this meeting takes place, a rehearsal of a play written about Auden and Britten is going on. Even the biographer of Auden, Humphrey Carpenter is a character in the play. Meta on meta, how does it work? See for yourself for five euros, online theater here: https://www.originaltheatre.com/portfolio-item/the-habit-of-art/

When I saw this play at the National, audience quickly grasped the characters, and the plot not much moving to any direction became irrelevant. The magic of the ethereal common compassion: however dark and complicated the characters are, we can’t judge, as we see ourselves.

One side comment. A play in a play is a device you think will never work, and yet it works in The Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hamlet and The Dresser (Ronald Harwood). Incidentally, Mel Brooks (Lubitch) comedy To Be Or Not To Be is one variant of this, and in Finland, a greatly loved Young Adult writer Rauha S.Virtanen made a great story on The Seagull in her book “Tuletko sisarekseni,” Oh. Chekhov made two play references in The Seagull: Konstantin’s play and Trigorin’s point of the seagull shot down, a nice, tiny theme for a play.

Last, but not least, the Auden biographer Humphrey Carpenter is a son of an Oxford Bishop. The little Humphrey was cycling around in the hall with his red tricycle when C.S.Lewis stormed out of the study of Bishop Carpenter, who tried to say/shout to Lewis: “There are RULES!” The Bishop didn’t agree to marry C.S.Lewis and the divorced Joy Gresham. Institutions clash in a very British way.

Kommentit

Tämän blogin kommentit tarkistetaan ennen julkaisua.